Female genital mutilation (FGM), is the practice of altering or injuring the female genitalia for non-medical reasons, ranging from partial or full removal of the clitoris and vulva to repositioning the labia over the vaginal opening.

FGM is not only a violation of a girl’s rights and autonomy, but it can also be incredibly dangerous and lead to lifelong complications. Immediate complications from the procedure include severe pain, shock, hemorrhage, infection and more. Each year, thousands of girls die while going under the knife, often due to hemorrhages or sepsis.

But even once the initial wound is healed, women and girls are not out of danger. Long-term consequences of FGM include potentially deadly complications during childbirth, anemia, infertility, painful intercourse or menstruation, and lifelong psychological effects.

There is no health benefit from female genital mutilation. Often, FGM happens as part of a religious or cultural ceremony to “protect” a girl’s purity, suppress her sexuality, or increase her fertility. The age at which girls come under the knife varies between cultures, ranging from when girls are newborns to when they reach puberty.

FGM is internationally recognized as a human rights violation and outlawed in several countries – but it is still an incredibly pervasive practice. An estimated 230 million women and girls alive today are survivors of female genital mutilation. Nearly 4.4 million girls are projected to be at risk of FGM in 2025 alone.

Survivors and impacted loved ones of FGM tell their stories

“I lost my baby in front of my eyes. I began to question why she was killed in this brutal way for being a girl.”

Safia was 22 when she found out she was pregnant – and she and her husband were overjoyed. “The news brought a lot of joy. We were very excited to become parents.”

However, the joy of safely delivering her baby girl turned into a nightmare all too quickly. Three days after her daughter’s birth, Safia’s mother-in-law showed up with tools to perform FGM on the newborn. Safia, who was a survivor of the procedure herself, was told by her mother-in-law that it would “allow the child to lead a moral life”, so she agreed to the procedure.

But her child did not survive the surgery.

“Her death not only killed my joy of being a mother, but killed me a thousand times over,” Safia shared with us afterward. She was devastated by the loss and blamed herself for not saving her daughter, though FGM was so engrained in her culture that she didn’t know to question it.

When she became pregnant again with a girl, she decided that she would do whatever was needed to spare her daughter from the same fate. She spoke to neighbors who had decided to abandon the practice of FGM and were directed to a UNFPA safe space. There, Safia, her husband, and her mother-in-law learned of the true dangers of FGM and were convinced to permanently abandon the practice in their family.

“I saved the life of my second daughter,” Safia shared. “With this awareness, I believe I can help spare the lives of many innocent girls.”

“She mistakenly thought the woman was aiding in the childbirth.”

Napala had little reason to worry about being forced to undergo FGM. In her ethnic group, the Karamojong, FGM was not practiced. And though her husband was from an ethnic group that did still practice FGM, he had no interest in subjecting her to that custom. But tragically, his mother had other ideas.

When Napala’s contractions with her first child began, her mother-in-law took her to the hospital, but they were instructed to come back later when her labor had progressed a bit more. On the way home, Napala’s mother-in-law insisted they stop to rest at the nearby home of a friend. Napala entered the house willingly, not knowing that the woman was both a traditional birth attendant and a practitioner of FGM.

When Napala’s labor progressed, she asked to return to the health center, but was convinced by her mother-in-law to stay at the woman’s house and deliver the baby there. Napala labored for hours, and it was during intense contractions that the practitioner removed Napala’s clitoris and inner labia.

“Napala was oblivious to the act,” her sister, Josephine, said. “She mistakenly thought the woman was aiding in the childbirth.”

Napala began to hemorrhage, and the woman fled. She was rushed to a hospital, but it was too late: both she and her baby died before they could receive care.

Napala’s entire village grieved her loss and recommitted themselves to the fight to end FGM. Josephine became involved in a UNFPA project to end FGM in the region, sharing her sister’s story as proof of just how deadly the practice can be.

“That day, I experienced fear, deception and excruciating pain. I was only seven.”

Nearly five decades ago, Dania underwent FGM against her will – but she still recalls every moment.

““’Come with me, we need to go to the bakery’, my mother told me one morning. When we arrived at the bakery, my mom took me to the back room where there was an old stove. I saw an old woman holding razor blades. I remember that old woman and my mom holding me down. Words cannot express the pain and confusion I felt.”

The scars healed, but the trauma of the event remains. Today, Dania is an advocate of ending FGM in her community, as well as the gender-biases that drive it,

“By performing genital mutilation and other harmful practices, we are robbing our daughters of their sexual and reproductive rights,” Dania shared with us.

Our work to end FGM

Female genital mutilation is a direct violation of the inherit rights, dignity, and autonomy that every woman and girl possesses. As the United Nations Sexual and Reproductive Health Agency, we’re dedicated to securing a future where there are zero incidents of violence against women, and putting an end to FGM is a significant part of that goal.

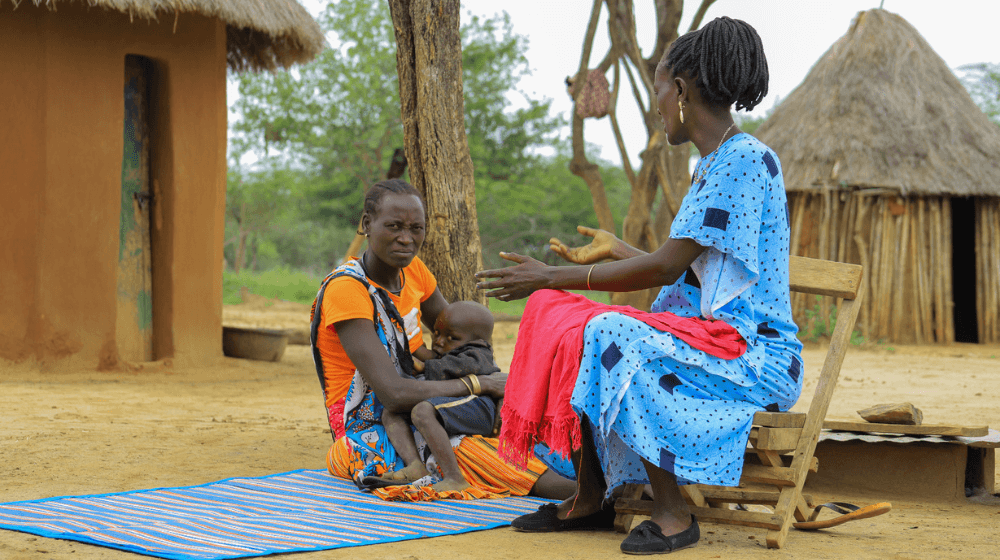

But ending FGM is not as easy as convincing lawmakers to ban it. We must educate people on the dangers of FGM and change cultural understandings of FGM, one community at a time – and that’s exactly what we’ve done.

In Egypt, we’re engaging men and boys to become advocates against FGM and help put an end to FGM in their communities and households. In other areas, we’re talking directly to female genital mutilation practitioners to explain the dangers of FGM and train them up on alternate income generators, such as midwifery. Around the world, we’re opening “Generation Dialogues” which initiate social and behavioral change toward FGM one community at a time.

In 2023, these efforts resulted in 162,000 girls being protected from female genital mutilation.

We’re incredibly encouraged by the amount of progress that we’ve made so far in putting an end to female genital mutilation, but continued progress is never guaranteed – especially as we face funding uncertainty from the U.S. government.

Right now, the U.S. government has suspended all funding to foreign aid, meaning that, at the time of writing this, we are receiving $0 toward our lifesaving projects. If you would like to make an emergency donation to keep our work, you can do so here.