What Dr. Ambereen Sleemi Saw During Her Month-Long Tenure at Gaza’s Nasser Hospital

After nearly two years of war in Gaza, the entire region has been devastated.

More than 60,000 people have been killed, two-thirds of whom are women and children. Nearly 2 million people are currently displaced, many multiple times over. Fewer than half of all hospitals in Gaza are at least partially operational, and critical healthcare services such as childbirth care are in a freefall. One in three pregnancies is now high-risk, and there has been a 300% increase in miscarriages and childbirth complications.

For nearly two years, it has been nearly impossible to carry a healthy pregnancy in Gaza—and now, famine has been confirmed in parts of Gaza.

Getting aid into Gaza has been difficult, getting much-needed healthcare workers has been even harder—but Dr. Ambereen Sleemi refused to relent in her efforts to bring her medical expertise to Gaza.

Dr. Sleemi, a passionate member of USA for UNFPA’s Leadership Council, is a pelvic medicine reconstructive surgeon (urogynecologist) who is also trained in obstetric fistula surgery and OB/GYN medicine. Recently, she returned from a three-and-a-half-week tenure at Gaza’s Nasser Hospital.

This is what she saw while working in Gaza’s last fully operational hospital.

Dr. Sleemi’s Journey Into Gaza

“I tried to get on a roster for well over a year,” Dr. Sleemi began. “There’s a limited number of spots, and an OB/GYN was not a top priority. But I kept making the argument that we still need to take care of women.”

After months of waiting, Dr. Sleemi found out that she had been selected to go to Gaza with little time to prepare. In just a couple weeks she was flying into Amman, Jordan with just enough food to herself (no extra food was permitted) and a small number of only personal items that were allowed. She was placed on a bus with other aid workers to travel into Gaza, and the bus was repeatedly stopped for screenings and checkpoints. The journey, which should’ve taken three hours, took fifteen hours.

Then, they arrived at the wall between Gaza and Israel.

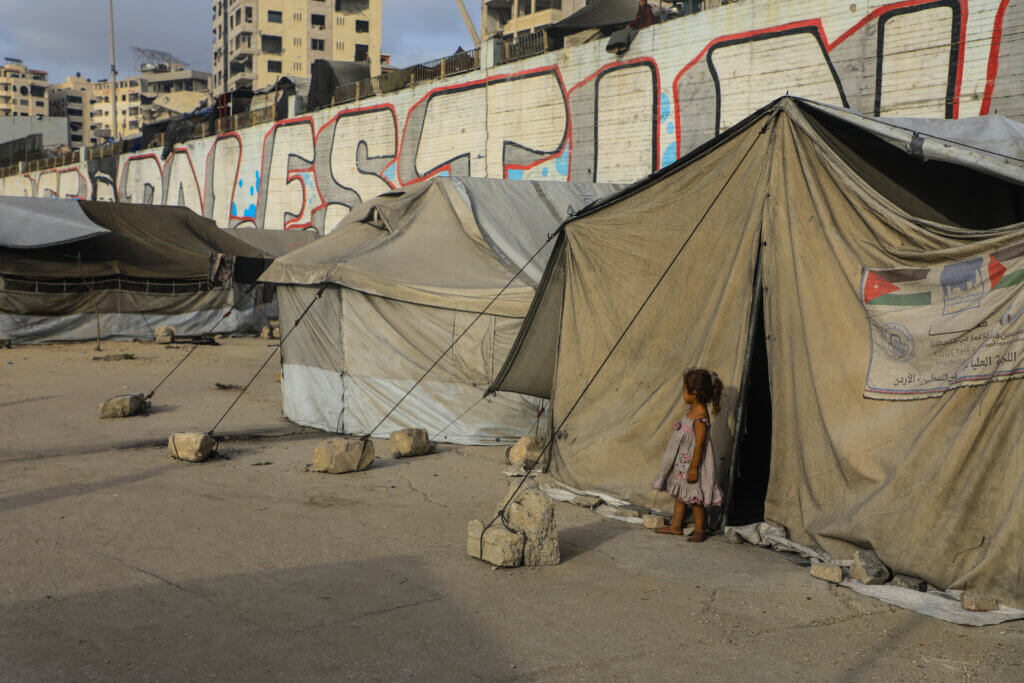

“You’re at the wall where, on one side, there’s this irrigated lush land. And then on the other side, it’s dusty and just a paved parking lot with armed guards and armored UN vehicles.” Dr. Sleemi shared. “A convoy goes through and then you’re in the middle part of Gaza. You see how everything is bombed and razed to the ground.”

Dr. Sleemi was picked up by a host group and taken to Gaza’s Nasser Hospital—a building that was hit in multiple airstrikes just one month after she left.

A Dire Lack of Supplies and Resources

Immediately, Dr. Sleemi was confronted with an overwhelming number of starving patients who needed advanced medical care and a hospital that had only a limited number of supplies.

“There were a remarkable number of injuries from burns and shrapnel. The trauma rate was astronomical already—and throw on top of that the malnutrition and food scarcity that every person was facing. Just starvation alone would make people of all ages critically ill.

The number of people needing medical intervention or nutritional support has multiplied. With the blockade, there has been a shortage of medications, wound care supplies, dressing changes, anything that a hospital needs to function. “

Dr. Sleemi went on to say that prenatal vitamins and family planning supplies simply didn’t exist in Gaza anymore. Starvation, stress, and lack of healthcare had caused a significant increase in miscarriages, birth defects, and stillbirths. Every single day, the team was forced to make an impossible decision on how to use the limited resources that they had.

“When we did bedside rounds, we had to make tough decisions. For example, if a woman is at risk of pre-term labor, do you keep her pregnant for another week for her baby’s sake, or do you induce her now while she’s guaranteed a bed and there isn’t an active evacuation? How do you triage a limited amount of supplies and medicine? Who gets discharged and who gets admitted?”

“This is all in civilian populations,” Dr. Sleemi added grimly.

Treating Patients in War

Around the clock, Dr. Sleemi treated patients experiencing devastating traumas and malnutrition.

“I treated a pregnant mother with a gunshot through her abdomen,” she told us. “I have seen babies brought in starving and malnourished, unable to be saved. Numerous pregnant women came in with terrible burns and shrapnel wounds—even in alleged safe zones.”

One patient in particular stayed with her.

“I treated a woman who was five months pregnant. She was sleeping in a tent with her husband and children in what was supposed to be a safe zone, but a bomb was dropped in the area. Her husband was killed instantly, and her children were either killed or heavily wounded. She came in with extensive burns, explosive injuries with shrapnel, and loss of vision in one eye. She couldn’t breathe because of the smoke and fire. She needed extensive surgery for her burns, including skin grafts and abdominal surgery to remove the shrapnel.”

We intubated her immediately. She was so malnourished I could hardly tell she was pregnant, but I performed an ultrasound and confirmed that her baby was still alive. At first, we had the hope that she and her baby would pull through.

I checked in on her a few times after leaving. A couple weeks ago I found out that she had passed away.”

Speaking about the overall weight of the impossible decisions she had to make every day and the traumas she was unable to treat, Dr. Sleemi told us: “It was difficult to see. But the truth is, I was only there for three and a half weeks.”

Healthcare Workers in Gaza: The Heroes That Show Up Every Day

“What inspires me beyond belief—and gives me hope in this terrible circumstance—is the doctors, nurses, midwives, and medical staff who have been working to get the healthcare system afloat for the last 22 months,” Dr. Sleemi told us.

Since the conflict began, 1,500 healthcare workers have been killed. In the time she was in Gaza, a well-known OBG/YN was bombed in his tent. Another well-known surgeon was killed.

“I once spoke with a specialist who said that doctors in his specialty used to not be so rare, but too many were killed,” Dr. Sleemi shared.

But not only were healthcare staff just as vulnerable to attacks as the people they were treating, they too were starving.

“My fellow doctors and medical staff would use their breaks to plan how they would find food for themselves or their families. While I was there, the World Central Kitchen ran out of food for the healthcare workers. Everybody would talk about how hungry they were.”

And yet, despite the attacks that shook their tents at night and the hospital during the day, despite the frantic evacuations, despite also starving to death themselves, healthcare staff in Gaza continued to show up every day.

Final Thoughts

“I have so much guilt with leaving everyone behind, but who else is there to speak about the reality in Gaza? Beside the journalists on the ground, there are only aid workers and health workers.”

Dr. Sleemi has also worked as a humanitarian physician in other crises, including in Ukraine, Pakistan, and Nigeria. We asked her if experience in Gaza was different.

“My previous humanitarian work only partially prepared me for everything I experienced in Gaza,” she said. “Ukraine and Gaza are both tragic situations—but the one thing I can say for Gaza that is different is that there’s no safe place. We hear it all the time. Being there, it was completely evident that there is no safe place in Gaza. “

“The need is greater than ever in Gaza,” Dr. Sleemi added.

“UNFPA is one of the organizations delivering lifesaving care in Gaza—and one of the few who remain focused on pregnant mothers, women, and girls. They provide Dignity Kits that are one of the few sources of menstrual health products and other feminine health items. They deliver nutrients and vitamins to pregnant and breastfeeding mothers. They coordinate mental health services and referral services. They are there.”